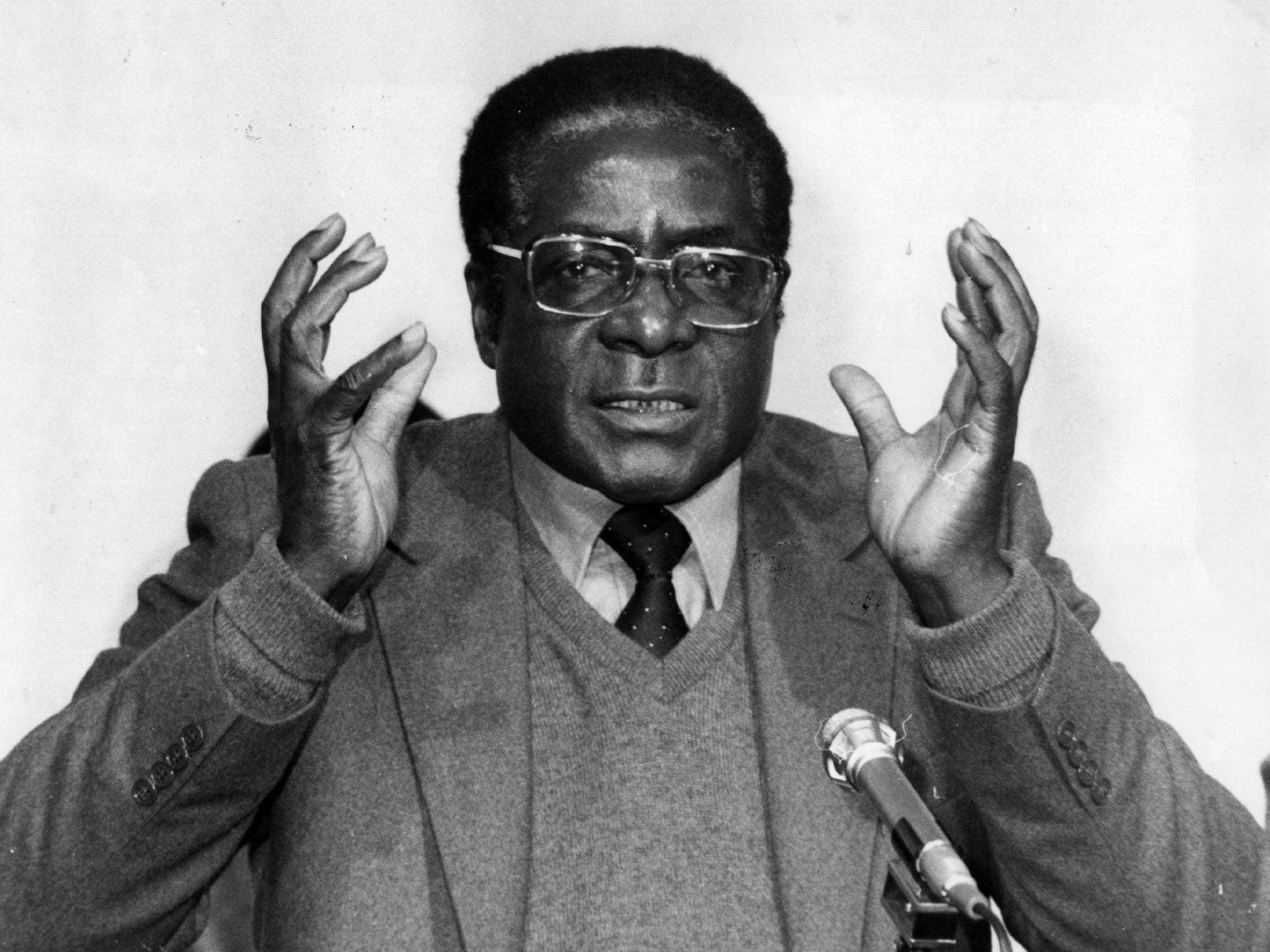

Robert Mugabe: After leading Zimbabwe to freedom, he then tore it apart

The despotic leader oversaw widespread corruption and human rights abuses. He leaves his country facing a bleak and uncertain future, writes Kim Sengupta

Robert Mugabe sat on a green leather chair in a pagoda-shaped pavilion in the garden of his home, Blue Roof, in Harare with his wife Grace standing behind him. Both were impeccably dressed, he in a navy suite, white shirt, tie and pocket handkerchief; she in a white top with a grey jumper.

There was a bank of microphones on a circular grey stone in front of them, and a group of journalists. We had rushed there in answer to phone calls announcing that the president of Zimbabwe had decided to hold a press conference.

The gathering was the last memorable public appearances by the man who had ruled his country for 37 turbulent, often bloody years – years that ranged from the heady promise that came with the breaking of colonial chains to a divided and despoiled land.

Mugabe, one of the most well-known leaders in the world, the man who led his country to freedom, and who then oversaw it falling apart as he turned into a despot, is dead at the age of 95. The Zimbabwe he left behind faces an uncertain and bleak future.

Mugabe had already been overthrown 12 months earlier in a combination of a coup and street protests, and his call to the media in July 2018 came in the last days of the election campaign to find his successor.

Initially relaxed and then angry, he railed against his enemies: the military who had once brutally crushed dissent, and his party, Zanu-PF, which had, over the decades, rigged the electoral process to keep him in power, before ultimately removing him from the throne.

“I can’t vote for those who tormented me, no I can’t ! I can’t!” said Mugabe, raising his fist as he decried his former political comrades, before praising the main opposition candidate, Nelson Chamisa, of the Movement for Democratic Change (MDC), a young man who said he was modelling his run on Donald Trump.

Mugabe resignation celebrations – in pictures

Show all 7Grace Mugabe, his former secretary, 41 years younger than him, smiled encouragement. Claims of corruption and venality against the woman, accompanied by the nicknames of “DisGrace” and “GucciGrace”, had added to Mugabe’s unpopularity – and her ambition of power was one of the reasons behind the army carrying out the putsch.

“I do not accept the denunciation and vilification of my wife that is going on every day. Leave, leave, leave my wife alone. I want Grace to remain my Grace,” cried Mugabe, slumping forward suddenly, exhausted, as she patted him on the shoulder.

Despite the public anger and accusations of malpractice against her, Grace Mugabe had remained free. The protection had been largely due to her husband, who, despite his fall, had a special status as the leader who led the nation to independence.

What happens now, after Mugabe’s death in Singapore, remains to be seen. Emmerson Mnangagwa, who won the election and is now president, once had to flee to exile in South Africa after incurring the wrath of the First Lady. There is speculation whether the veteran survivor, who has a reputation for ruthlessness – and the sobriquet of “crocodile” – will take his revenge at last.

The fall of Mugabe had led to citizens pouring out on the streets of the capital. There were calls for a “Day of Rage”, but it soon became a day of celebrations where everyone, including us in the foreign media, were made to feel welcome. The police, blamed for graft and heavy-handedness, kept away. But there was little or no trouble, and it felt, with the infectious exuberance, that a new page had been turned.

Women and men, the young and elderly, danced, sang and waved the national flag. They carried placards saying: “Mugabe just go”, “Mugabe leave Zimbabwe now”, “People v Robert Mugabe”, “Red Card for Mugabe,” and, at a place where they avidly follow English Premier League football, “Mugabe worse than Moyes” – and “Wenger must go”, for good measure.

But that mood did not last long. The deep fractures of the Mugabe reign were not slow to surface. In the days following the bitterly contested polls, which the MDC claimed were fixed, we saw troops go on the rampage, using live rounds and bayonets on the streets of the capital after protests had been largely dispersed by police using teargas, baton rounds and water cannons.

The following day we met people injured, shot, stabbed, and beaten with sjamboks – the heavy rhino-hide whips favoured by security forces of apartheid South Africa – gouging out deep scars.

Vimbai Maburutse, a 28-year-old MDC activist receiving treatment for sjambok cuts, was among those who felt the Mugabe times had returned almost as soon as they were supposed to finish.

She and others were crouching behind a car trying to shield themselves from street battles around them, when soldiers running by stopped and opened fire.

“They were shooting into the car, they could see there was no one inside, but they were trying to hit us through the windows. Our own army was being used to try and kill us, it’s very sad,” she said.

She started running and was then whipped until she fell to the ground. “How is this any different from Mugabe times, we are asking ourselves, and we don’t think it is,” she said.

That question was asked many times in the months that followed. The beginning of the year saw violence erupt again after the doubling of fuel prices and a rise in the cost of other essential commodities. The subsequent crackdown led to more than a dozen people killed, 80 treated for gunshot wounds, more than 700 arrests – including 11 opposition MPs – and doctors reporting evidence of “systematic torture” of prisoners.

During another round of strife last month, after a court banned marches planned by the opposition, around 100 people were arrested in Harare after baton charges and the use of tear gas. Civil society groups claimed members had been abducted and tortured by masked gunmen.

Severe drought and a cyclone have added to the economic woes. In June, the UN estimated that more than five million people – a third of the country’s population – would need humanitarian assistance by the end of the year. The World Food Programme (WFP) stated in its August report that two million people were facing starvation.

The death of the nation’s first leader, declared Mr Mnangagwa on Friday, was the loss of “an icon of liberation, a pan-Africanist who dedicated his life to the emancipation and empowerment of his people”. He said: “His contribution to the history of our nation and continent will never be forgotten. May his soul rest in eternal peace.”

Monica Mutsvangwa, the minister of information, added: “Yes, it is really saddening. Some of us were like his children to him. We can never write our history without mentioning him.”

Mr Chamisa, the opposition leader, said: “Even though I and our party, the MDC, and the Zimbabwean people had great political differences with the late former president during his tenure in office, and disagreed for decades, we recognise his contribution made during his lifetime as a nation’s founding president.”

Others in opposition expressed varying degrees of forgiveness.

Tendai Biti, a former finance minister, said: “He failed to make the transformation from a liberation leader to a national leader. The war did not end for him in 1979. He tortured me and killed thousands and thousands of people. But I am not bitter, he was a product of his time.”

For David Coltart, a founding member of the MDC, Mugabe “will be remembered for ending white minority rule and expanding quality education ... But one just cannot ignore the evil which occurred during his rule – the negative aspects of his legacy live on”.

For many of the ordinary people of the country, striving to cope with daily hardship, there was little positive in the legacy.

Mugabe will be remembered for ending white minority rule and expanding quality education ... But one just cannot ignore the evil which occurred during his rule. The negative aspects of his legacy lives on

Precious Tawanda, a 53-year-old teacher in Harare, has to work two other jobs to help feed her family.

“I was young when we got independence – people were happy, there were good dreams for the future. But those dreams have long gone, I can tell you, and we just feel bitterness now,” she said.

“I got a good education and it was free. But what has it got me? I cannot even get a wage to live on. I am a teacher now, I think, ‘What will happen to the boys and girls I am teaching? Will they get jobs?’ I don’t think so. That is because Mugabe took a country with a good economy, one of the best in Africa, and he ruined it.”

Mugabe, who had been jailed by the colonial powers and got much of his education in prison, won the post-independence election in 1980 by a landslide.

It was not the result that Margaret Thatcher or her foreign secretary, Lord Carrington, had expected and there was trepidation among many in the country’s white community.

But Mugabe’s first address to the nation was one of reassurance and reconciliation, stressing repeatedly that Zimbabwe in freedom would be a home for all its people. The white community seemed mollified. Ian Smith, the leader of Rhodesia’s UDI government, which had imprisoned so many black nationalists, faced no retribution, and continued life as a farmer.

But retribution was taken against some of his former rivals in the liberation struggle, especially Mugabe’s main foe, Joshua Nkomo, and his followers. From 1982 to 1987 Mugabe sent the North Korean-trained 5th Brigade into Matabeleland in the east, claiming that a rebellion was brewing there.

The Ndebele population of Matabeleland claimed that up to 40,000 were killed in what became known as the Gukurahundi massacres in those years. The International Association of Genocide Scholars estimated the death toll at 20,000. The International Committee of the Red Cross documented 1,200 deaths in one month, February 1983, alone.

Mugabe’s powerbase among his Shona community remained high and he won the 1985 election with some ease. Internationally, too, his stock remained high and claims of civil rights violation did not cause much impact. In 1991, the Commonwealth issued the Harare Declaration of Human Rights, which was meant to be a benchmark for member states.

But the issue of land ownership was rumbling on behind the scenes. A drought and subsequent food shortages in 1992 brought focus on the emotive issue, and renewed demands for land for the guerrilla fighters who had freed the country and their families. A Land Acquisition Act was passed by the Mugabe government but not enforced.

Two-thirds of the arable land continued to be under white ownership. The white owners stressed that they had made the farms commercially productive, the “bread basket of Africa”, and provided a major source of employment.

Mugabe had been asking successive British governments to fund a compensation scheme for land redistribution but failed to get their support. In 1997, he was curtly rebuffed by Tony Blair, triggering the Zimbabwean leader’s bitter antipathy towards the British prime minister.

Mugabe was facing increasing clamour for land from his followers and made his move on the farms that year – the takeovers began.

The worsening situation, many feel, could have still been managed, but the Zimbabwean leader was distracted by a foreign adventure – sending forces into the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC). This ensured that Mugabe retained the support of the generals who were enriched by the looting of the mineral resources going on there, but the costs of the military operations further damaged a rapidly wilting public purse.

Zimbabwe did not recover from what went on at the time. The economy disintegrated, but Mugabe hung on to power, at times with power-sharing deals with opposition figures.

With little to look forward to in the future, the bitter enmities of the past are remembered in Zimbabwe, along with the bitter feeling among many that nothing much will change.

President Mnangagwa was very much a member of Mugabe’s inner circle until his falling out with Grace Mugabe. His first big job was as minister for national security in which he controlled the intelligence service, the Central Intelligence Organisation.

It was during his tenure that the bloody Matabeleland campaign and Gukurahundi took place. Mnangagwa had been publicly accused by opposition politicians and human rights groups of being involved in the massacres, and even of orchestrating them, something he has repeatedly denied.

In one of his last statements on the matter, he said: “How do I become the enforcer of the Gukurahundi? We had the president, the minister of defence, the commander of the army, I was none of that.”

But many in Matabeleland remain convinced of the culpability of some in the current government.

Jonathan Mkhwansanzi, a 29-year-old businessman, lost his father in one of the massacres. “He was an innocent man and he was killed for nothing and there has never been any justice,” he said at his home in Bulawayo. “There are people in power who bear guilt and the hatred is still there. Mugabe may be dead, but his spirit will not go away.”

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments