Stargazing in July: The heart of the scorpion

If you get a chance to view Scorpius in its entirety, you’ll see it’s one of the few constellations that resembles its namesake, writes Nigel Henbest

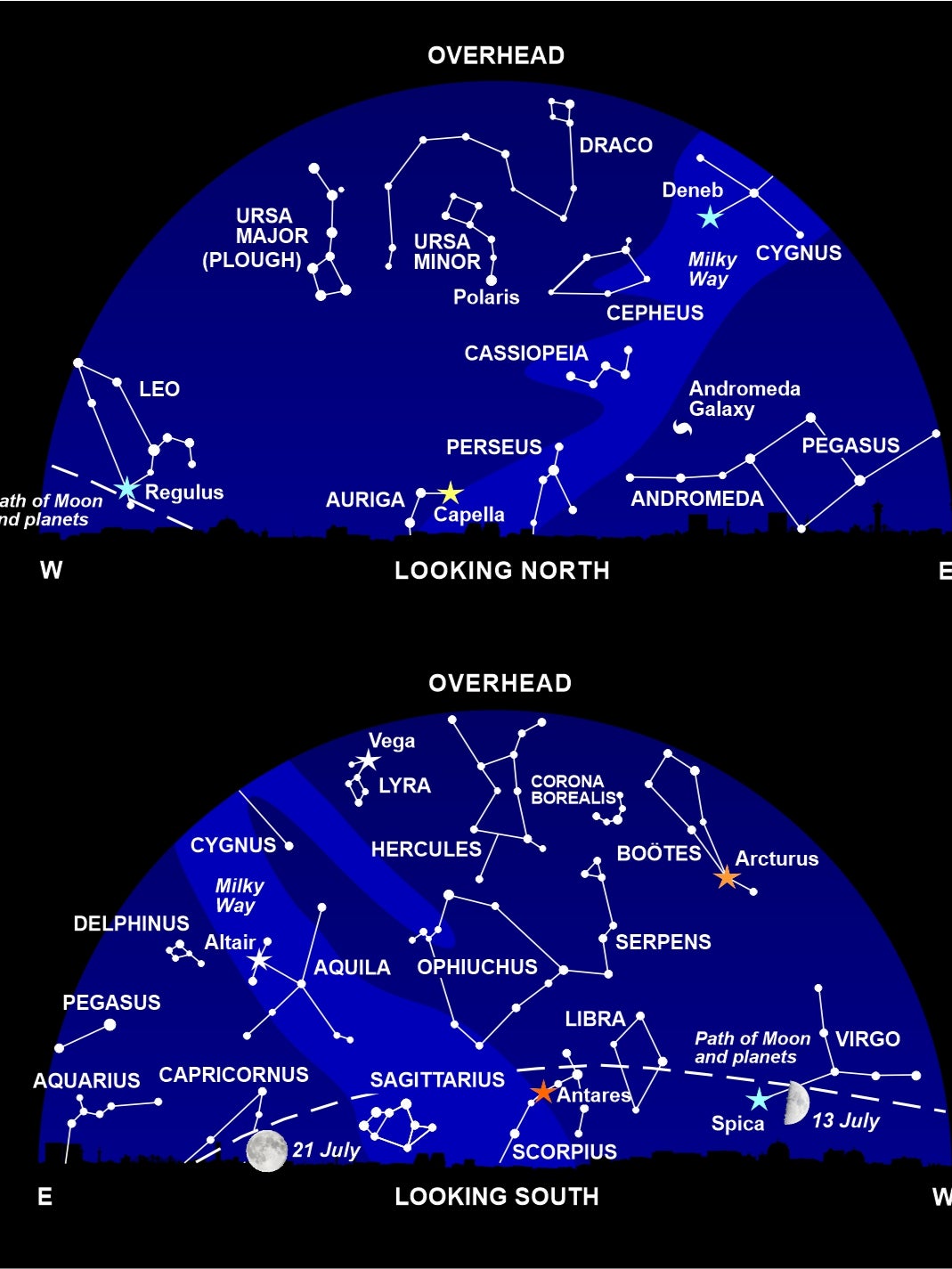

Low in the south this month lurks a truly amazing constellation – a wonder of the sky for anyone living south of the equator, but sadly truncated by the horizon for those who reside in latitudes as far north as Britain.

I’m talking about Scorpius, the celestial scorpion. If you get a chance to view the star-pattern in its entirety, you’ll see it’s one of the few constellations that resembles its namesake, with claws at the top right and a body that stretches downwards to curve around in a distinct tail with two bright stars marking the sting at its tip.

In western sky-lore, these stars have been seen as a scorpion right back to the earliest written astronomical records, inscribed in Babylon before 1100 BC. To the ancient Chinese, these stars were the backbone of the Azure Dragon of the East. Polynesian navigators in the Pacific saw this curved line as a fishhook, which pulled up the Milky Way as it rose from the ocean and ascended into the sky.

In Greek mythology, the scorpion was the nemesis of the mighty hunter Orion. When Orion boasted that he could slay any living creature, a sneaky scorpion crept up and fatally stung him in the ankle. To commemorate man and beast, the gods raised both into the sky as constellations – but at opposite ends of the heavens, so they can never be seen at the same time: Orion is glorious in the winter sky, while Scorpius sparkles during the summer months.

Rivalry between Orion and the scorpion continues on the astronomical stage. Both star-patterns are replete with more than their fair share of beauty spots: Orion boasts a great nebula where stars are being born, while Scorpius is rich in scintillating star clusters. And both have a supersized red giant star, vying for our attention.

Betelgeuse – in Orion – is probably the best-known star in the sky: say ‘Beetlejuice’ and most people’s faces light up in recognition. Yet Scorpius has a near twin that I would say is even more interesting.

Antares marks the heart of the celestial scorpion: fittingly, it’s blood red in colour. Though the star’s name is Greek for ‘the opponent of Mars’ Antares is the clear winner as it has a far ruddier hue than the ochre-coloured red planet.

Both Antares and Betelgeuse are around 15 times heavier than our Sun and 70,000 times brighter; both stars have swollen in their old age to become red giant stars, 650 times wider than our local star. If you plonked either into the centre of the Solar System, they’d engulf all the planets out to Mars, plus the asteroid belt. And both stars will soon explode as supernovae, shining in our skies as brilliantly as the Full Moon (though ‘soon’ to astronomers means any time in the next 100,000 years.)

Unlike Betelgeuse, Antares isn’t alone in space. Through a moderately powerful telescope (you’ll need an instrument with a mirror 200 mm in diameter or more), Antares B appears as a minuscule emerald next to a brilliant ruby. No other star in the sky is green; and by analysing the light from the Antares B, astronomers can tell it’s actually a blue-white star. The viridescent hue is merely a contrast with Antares’ strong red colour.

Antares B may live in the shadow of showy Antares, but it’s no celestial lightweight. This star is seven times heavier and 3,000 times brighter than the Sun. If it was its own in space, we’d see it with the naked eye even at a distance of 550 light years.

What’s Up

The planets are back! After a couple of months largely hidden in the Sun’s glare, most of our fellow worlds are back on display in July. First off the marks is Mercury: at the beginning of July, look low on the northwestern horizon at dusk (preferably with binoculars) to catch the elusive innermost planet. On 7 July, Mercury forms a striking pair with the narrow crescent Moon.

Saturn is rising in the east about 11pm, with the Moon lying nearby on 24 July. It’s followed at 1am by Mars, shining a tad less brightly. On the morning of 15 July, you can use Mars as a signpost to the dim planet Uranus: with binoculars or a small telescope, look about one Moons-width to the upper left of the Red Planet, and you’ll spot Uranus as a faint blue-green "star."

Brilliant Jupiter clears the horizon about 1.30am. As the Moon sails over the giant planet on the mornings of 30 July and 31 July we’re treated to some gorgeous groupings of Jupiter and the crescent Moon with the Pleiades, Aldebaran and Mars.

On the starry front, the southern sky is filled with the faint stars outlining the sprawling giants Hercules and Ophiuchus. They’re surrounded by a ring of variously coloured stars: clockwise from the horizon we have pure white Altair and Vega; orange Arcturus; blue-white Spica; and the ruby gem of Antares.

Diary

5 July, 11.57pm: New Moon

6 July, 6.06am: Earth at aphelion (furthest from Sun)

7 July: Moon near Mercury

9 July: Moon near Regulus

13 July, 11.48pm: First quarter Moon near Spica

17 July: Moon near Antares

21 July, 11.17am: Full Moon

22 July: Mercury at greatest elongation east

24 July: Moon near Saturn

28 July, 3.51am: Last quarter Moon

31 July: Moon near Jupiter

Nigel Henbest’s latest book, ‘Stargazing 2024’ (Philip’s £6.99) is your monthly guide to everything that’s happening in the night sky this year

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments